Tradition and resistance.

The church has a rich and interesting history. The land on which the church stands was made over to the British Crown by deed of gift in December 1900, and the external structure was completed by 1914. The interior furnishings had been ordered from England however, and it was not until after the end of the First World War that work was finally finished. Easter Sunday 1920 saw the first service to be held in the new church, which was finally dedicated by the Bishop of Gibraltar on the 5th of November 1922.

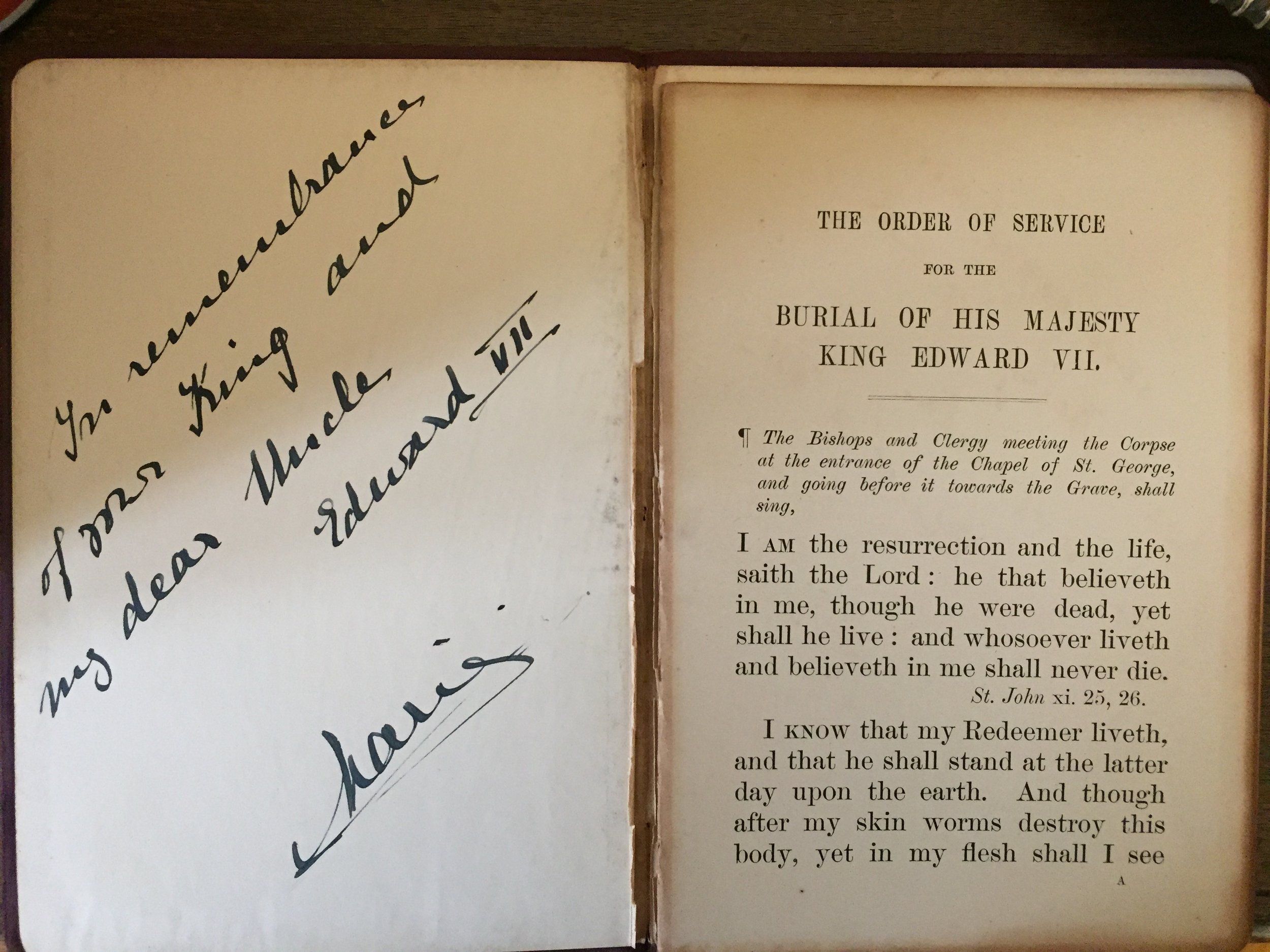

A regular attendee in the early days was Queen Marie of Romania, a granddaughter of Queen Victoria. After her marriage to Crown Prince Ferdinand, she continued to attend the English services in Bucharest, and it was largely thanks to her support that the present building was completed. Various members of the Royal Family have attended the church at different times.

A wooden panel at the back of the church records the names of the chaplains over the years, with a telling break from 1940 to 1966. In fact, the church was far from inactive during these “blank” years of World War II and the Stalinist period, during which Eastern Europe experienced such trauma and suffering. Although closed after the Christmas Day service 1940 until Christmas Day 1944, the church thereafter managed to maintain worship, with visiting priests from as far afield as Vienna and Malta. 1966 saw the establishment of a full-time chaplaincy, with emphasis on theological study and ecumenical contacts. Among those who held the post during this period was the Rev. Dr. David Hope, later Archbishop of York.

During the 1970s, at a time of increasing secularisation in Western Europe, it was suggested that the church might be better used as a library and conference hall for the British Council. Happily the proposal was resisted, and the church has the distinction of being the only Anglican church building in the former Eastern block countries to have remained open throughout the post-war Communist period.

Life became increasingly harsh for most Romanians during the 1980s. Even for members of the diplomatic and business communities movement was restricted and surveillance was constant. In 1983, the chaplain Robert Braun wrote that there was “no harassment from the authorities other than a security van which occasionally positions itself outside the doors on Sundays to photograph the worshippers”. The few Romanians who dared to worship at the church risked losing their job, their home, even their freedom.

Over the years since the fall of Ceausescu there have been enormous changes in Bucharest. The service at the Church of the Resurrection is no longer the only English-language Christian service available in the city. Nevertheless this distinctively British building, upon which the cross was “lifted high” throughout the years of struggle, is a landmark worth visiting. The congregation is a remarkably broad mix of people of different traditions, nationalities, and cultures, including a number of native Romanians. At a time when perhaps Europe as a whole is “in transition”, the Church of the Resurrection offers a visible example of continuity, combining tradition with ecumenical development and ongoing commitment to witness in the modern world.

(Adapted from a text by Fr. Chris Newlands)